Inside the mind of Joan Didion: The strangest and saddest book you will read all year

Hers was a celebrated literary life, set in and around Hollywood, where she was the queen of witty, uber-cool fiction. But a new book, ‘Notes to John’, which documents her most intimate therapy sessions, also shows a woman crushed by shyness and terrified of revealing what was truly tormenting her, says Robert McCrum

Most writers pick up their pens to make sense of the world in their heads, or the chaos around them. Their writing can become many things, bright or black; at heart, it’s always a genuflection to the cause of a creative equilibrium.

The California writer Joan Didion, who died in 2021, committed herself to this calling from an early age with exemplary zeal. Hers became a celebrated literary life, set in and around Hollywood. Yet, in what is possibly the saddest book you will read this year, we have a charcoal portrait of a writer and a mother at the end of her tether. Here, her shyness, which became a kind of paranoia, set her apart; all her life, she’d find it difficult even to speak “every day”.

The media twinned her with hell-raising American writer and artist Eve Babitz, but they were polar opposites. Babitz (Slow Days, Fast Company) revelled in LA as “better than Eden, which was only a garden”; for Didion, La La Land was “hell on Earth”.

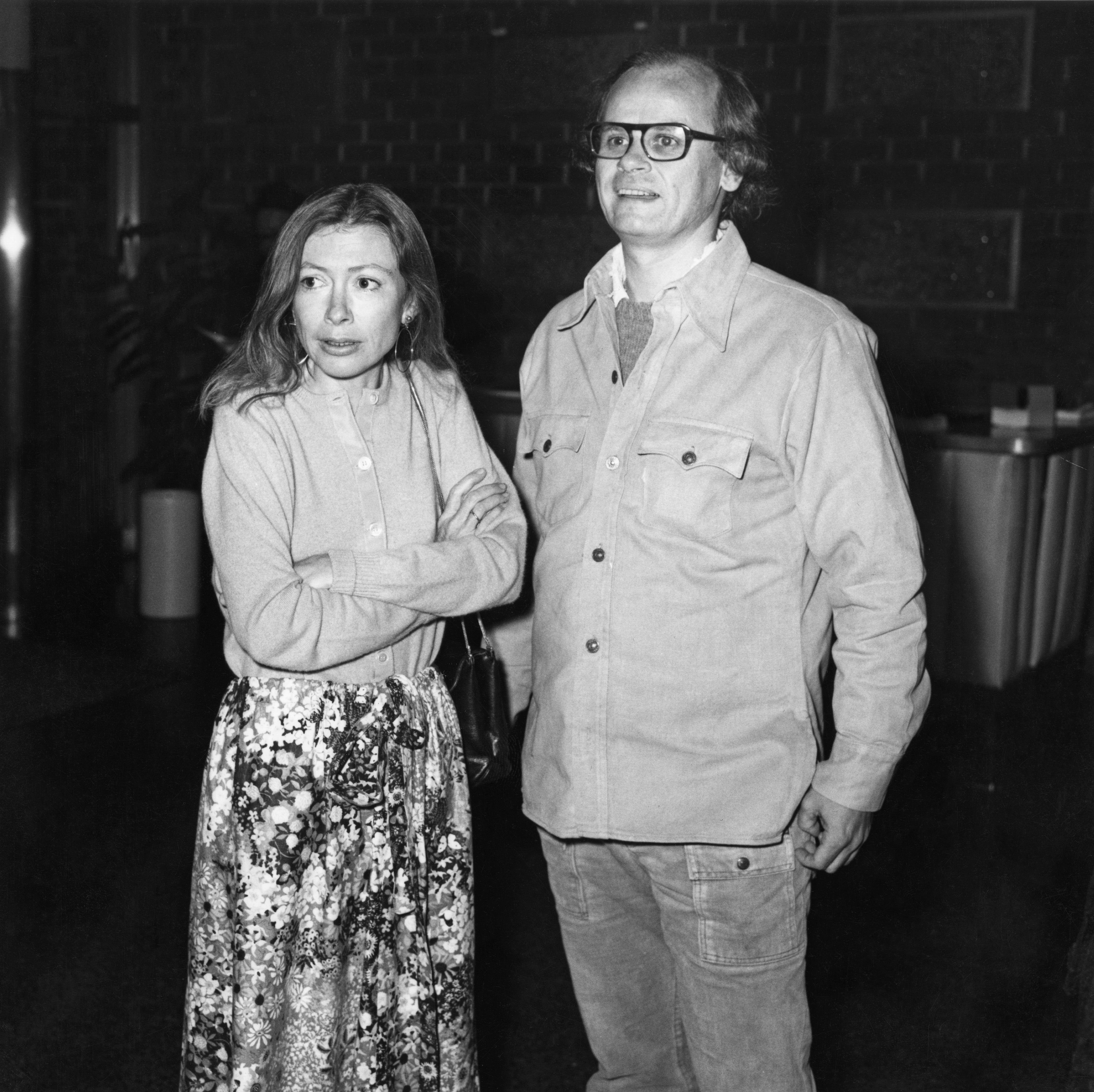

In 1964, she married the writer John Gregory Dunne (brother of the celebrated magazine journalist Dominick Dunne). Dunne wrote for Time, and Didion was an editor at Vogue, having started there in 1956 as a prizewinner. According to The New Yorker, theirs was “one of the most collaborative literary marriages in American history”.

She became the queen of witty, uber-cool fiction and journalism, fulfilling what she called “my little secret dream of being a writer”; she worked on movies with her husband, made a fortune from her contribution to A Star is Born, the 1976 Barbra Streisand movie smash, and established herself as a scarily fashionable American literary voice with Democracy, Play It As It Lays, and Slouching Towards Bethlehem.

It was a measure of her wealth and status that when she and Dunne resolved to curb their extravagant lifestyle, they “decided to address this in Paris, and take the Concorde”.

As in the case of her contemporary Tom Wolfe Jr, Didion’s work and persona became indistinguishable in a way that was typical of American literary culture: her personality and her prose were habitually praised for their “singular intelligence” or “precision and elegance”, clichés of criticism that resurface in the blurb for Notes to John. After the publication of A Book of Common Prayer (1977), Didion seemed to command the topmost heights of America’s Parnassus.

Hollywood can be a cruel place, and self-invention has its limits. Behind Didion’s gilded progress, there were demons. In 1966, after she had suffered a miscarriage, she and Dunne adopted a baby girl whom, in a nod to Mexico’s Yucatan, they christened Quintana Roo. This quest for a more complete family would become a heart-rending personal tragedy out of which, in the end, Didion’s writing would become a lifeline.

Every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. Didion, who disguised the afflictions of her disabling anxiety behind the pose she struck with her notebook, found her relationship with Quintana opening doors into an inferno of alcoholism, depression, guilt, and finally, terror.

In November 1999, after describing, with cool understatement, “a few rough years”, Didion arranged to undergo therapy with the psychiatrist Roger MacKinnon. Part of his treatment would be to explain how and why Didion had grown up “expecting the worst to happen”. In the airless cell of her marriage to a man with “a short fuse”, MacKinnon was a welcome voice of sanity: “You and your husband,” he said, “are going through hell.”

Some of Didion’s early work has been collected in a volume titled We Tell Ourselves Stories In Order to Live. Instinctively, having embarked on “the talking cure”, she wrote about her experience in weekly summaries of each session.

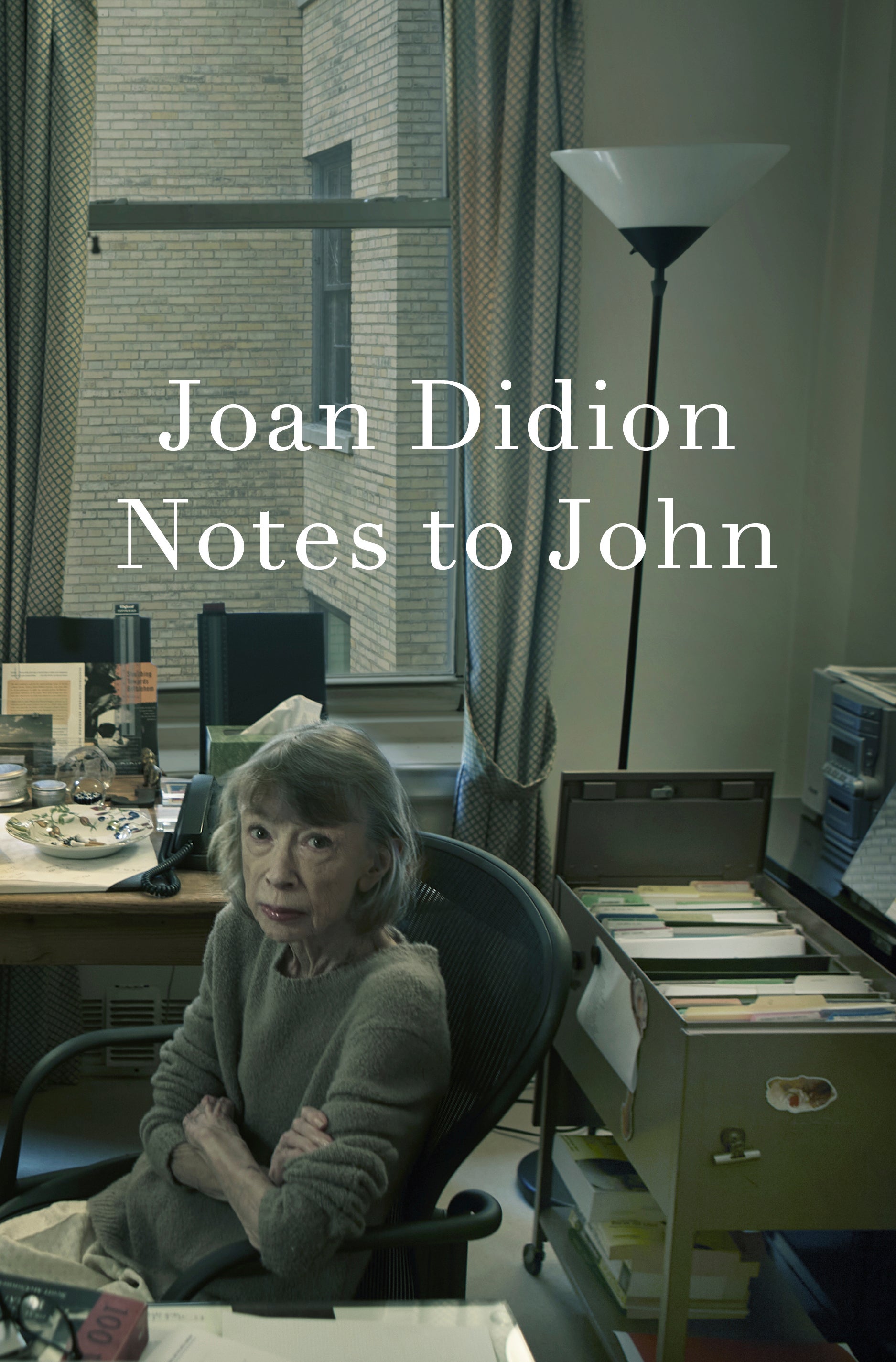

Notes to John, published last month by the Didion Dunne Literary Trust, is a semi-intimate record of her most tormented years with Quintana, a bleak window on her marriage to Dunne (there’s actually no “Dear John” in this manuscript), and – for those who are interested – the literary source for the three great works of Didion’s old age: The Year of Magical Thinking, Blue Nights, and finally, Let Me Tell You What I Mean.

In the last analysis, Notes to John is a disappointing as well as a shattering read. Didion’s estate has chosen to present these “150 unnumbered pages”, discovered in “a small portable file near her desk”, as she left them. There’s no clue as to her posthumous wishes for her most intimate thoughts about her husband, for example. The simple, quite chilly, unrevised text of her notes to Dunne is dated, but otherwise unexplained.

Possibly, this is Didion-esque. She freely admits to MacKinnon that she deals “with everyone at a distance”. With a few exceptions, Didion’s renowned wit is missing in action, but the overall effect – a voyeur’s experience of an analysis – is hypnotic.

Notes To John certainly contains many unresolved psychoanalytical issues. The book, lacking virtually any editorial intervention, leaves its readers to fathom for themselves the mysteries of Didion’s psyche, and her personal tragedy, with no clarifying textual apparatus.

Mostly, the reader must intuit the way in which analyst and analysed go about their work: an hour a week, remorselessly unpicking Didion’s childhood, the failure of her relationships with both her mother and her father, and the catastrophe of her own career as a parent – the distress of Quintana’s suicidal early adulthood.

The whole project has the mercenary air of a smash-and-grab raid by Didion’s executors on her legacy. Nothing new there.

And yet... there’s one unintended consequence of such negligence that’s fascinating. As much as a painfully unvarnished portrait of Joan-as-I-knew-me, this becomes a compelling, even affectionate memoir of shrink and shrinkee, a co-portrait of Roger MacKinnon, whose therapeutic couch Didion occupied from 1999 to 2012 (by which time MacKinnon was 85).

With him, Didion was not her cool self. At their first sessions, MacKinnon had seemed fazed by his celebrity client. “It’s as if you operate on a different level,” he said, before drily correcting himself: “Maybe it’s the entertainment industry.” Yet, on 11 October 2000, when the session began, she writes: “I sat down and immediately began to cry.”

He asked what was “on her mind”. Didion was clearly shocked at her tears. She goes on: “I said I didn’t know. I rarely cried. In fact, I never cried in crises.” It was, she confesses, in some of the most desolate words in this harrowing book, “very difficult to sit down facing someone and talk”.

When MacKinnon died in 2017, The New York Times described this veteran analyst as “one of the most skilled clinicians of his era”, an old-fashioned Freudian pictured in one magazine as “John Wayne in a blue suit”. He was certainly never afraid to shoot from the hip. “You make the mistake of thinking this is about Quintana,” he reproves. “It’s not. It’s about you.”

Sensible advice. It was only after many months of MacKinnon that Didion could resolve to get on with “living her own life”. In the end, it was to this reality that she’d have to return.

Notes to John ends abruptly in 2003, when the saddest part of this sad tale comes to haunt both Didion and her readers, the terrible coda to these “rough years” that only the dauntless candour of her writing could assuage. On 22 December 2003, Didion and Dunne’s daughter was rushed to hospital with pneumonia and was intubated, suffering from septic shock. This time she survived, but Dunne’s sudden death from heart failure, at the age of 71, followed on 30 December like the visitation of an ancient curse.

“Life changes fast,” Didion later wrote, in a much-quoted line. “Life changes in the instant. You sit down to dinner and life as you know it ends.” We will look in vain for such brilliance in this volume, but it unquestionably informs A Year of Magical Thinking. Blue Nights, about Quintana’s death aged 39, not two years later, is also an outcome of these pages.

Didion herself used to debate questions about her legacy with MacKinnon. “What’s it been worth?” she would ask, on the edge of desperation. Notes to John is part of the answer.

‘Notes to John’ by Joan Didion is published by Fourth Estate, £18.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments